April 25, 1992

- STAYED AT #1:8 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

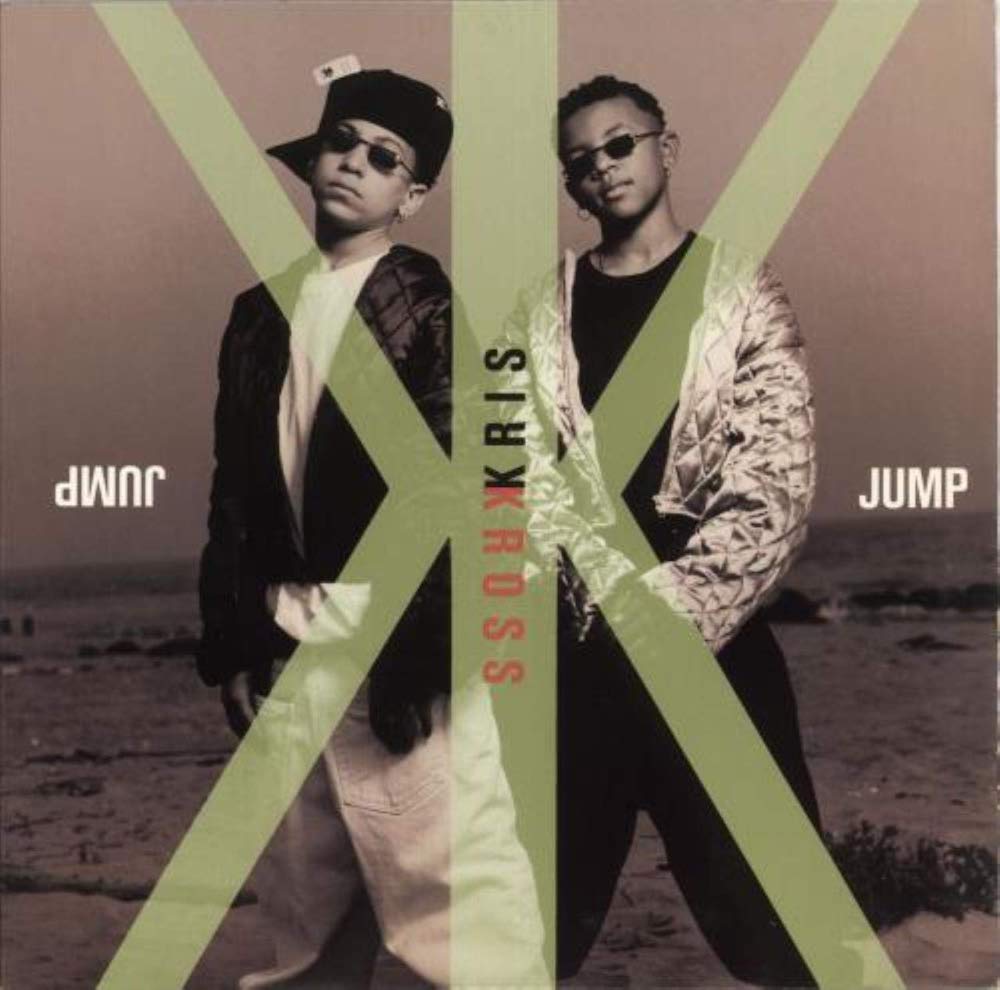

In retrospect, something like Kris Kross had to happen. By 1992, rap was easily the most exciting and vital genre of pop music. The kids in my little micro-generation had never really known a world without rap; the music was part of the air. But radio was scared of rap music. When rap songs first started crossing over and topping the Hot 100 in the early '90s, the stuff that made it to the top was carefully vetted for white consumption. Even though rap was unambiguously Black music, the first two rappers with #1 hits, Vanilla Ice and Marky Mark, were both blandly handsome white guys. When P.M. Dawn got there with "Set Adrift On Memory Bliss," their take on the genre was strange and psychedelic and daring, but their hit was also built on a sample of a new wave ballad, and the group stood in stark contrast to the fiery and militant rap that sat at the genre's vanguard at the time.

Those first three rap chart-toppers were different in all sorts of ways, but they were all, in one way or another, familiar. Those were all built on identifiable samples, and they all represented visions of the genre that white radio programmers might've found approachable. Kris Kross were different. They were a gimmicky kiddie-rap duo, and that alone made them unthreatening. But Kris Kross also made straight-up rap music. In terms of age and geography and subject matter, Kris Kross were outliers within rap music, but they still made music that could sit comfortably next to Public Enemy or EPMD in a DJ set. "Jump," Kris Kross' debut single and only #1 hit was, in its time, the most credible version of rap music that had ever made its way to the top of the Billboard Hot 100. In its time and for many years afterwards, "Jump" was also the biggest rap hit of all time.

"Jump" is a ridiculously catchy and memorable song, and that definitely helped it hit the way that it did. But the real difference-maker for "Jump" was probably timing. "Jump" was targeted directly at the kids in my micro-generation, the ones who had never known a pre-rap world. The two members of Kris Kross, Chris "Mac Daddy" Kelly and Chris "Daddy Mac" Smith, were parts of that exact same micro-generation. (I was born in September of 1979, the same month that "Rapper's Delight," the first rap song to reach the Hot 100, came out; both members of Kris Kross were about a year older than me.) If you were a little kid when "Jump" came out, then these two guys immediately seemed like the coolest human beings in existence.

While both members of Kris Kross were kids, they weren't really that much younger than the guy who discovered and assembled the duo. Jermaine Dupri grew up fully immersed in the R&B industry. Michael Mauldin, Dupri's father, was a road manager for funk acts like Cameo and the SOS Band. In the early '80s, a very young Dupri jumped onstage to dance with Diana Ross at an Atlanta show that his father booked. As a kid, Dupri found work as a dancer, touring with Cameo, Herbie Hancock, and early rap groups like Whodini and Run-DMC. Dupri was the little kid pop-locking in Whodini's 1985 "Freaks Come Out At Night" video.

Dupri was about 13 when he was in that Whodini video. Around the same time, he decided that he wanted to become a producer. Pretty soon, Dupri started writing and producing for an Atlanta girl group called Silk Tymes Leather. In 1990, when Silk Tymes Leather released their album It Ain't Where Ya From... It's Where Ya At, Jermaine Dupri was 18. That same year, Dupri was out at Atlanta's Greenbriar Mall, shopping with the three members of Silk Tymes Leather, when two little kids came up to them and asked for autographs. Silk Tymes Leather never made much of a national impact, but in Atlanta, still a rap backwater at the time, they must've been a big deal.

Chris Kelly and Chris Smith, both from Atlanta, had been friends since first grade. That day at Greenbriar Mall, the two of them were shopping for sneakers, and they walked up to Silk Tymes Leather to ask for autographs. Dupri, who wasn't too much older than those two kids, saw a whole lot of charisma in them. In Fred Bronson's Billboard Book Of Number 1 Hits, Dupri remembers the meeting: "They were real fresh. I thought they were some teen stars I wasn't hip to. So I said, 'Who are you? What do y'all do?' They said, 'No, we ain't no group.' Everybody else in the mall was looking at them the same way. People were paying attention." Right away, Dupri decided that these two little kids should be a group and that he should turn them into one.

Dupri came up with the deeply impractical trademark Kris Kross look, getting these kids to wear their jeans and baseball jerseys backwards. He also convinced his father to become the group's manager. Dupri produced a demo tape and shopped it around to labels. Most of them turned him down, but Joe Nicolo, a Philadelphia rap producer who'd recently co-founded the Columbia imprint called Ruffhouse, signed the duo. Ruffhouse, launched in 1990, had already seen some success with Tim Dog and Cypress Hill. Nicolo saw that Kris Kross were marketable -- they were two cute little kids who didn't cuss in their lyrics -- but also that they also came off tougher and meaner than a lot of the other pop-rap that was in the major-label system at the time.

The two Chrises didn't write their lyrics. Jermaine Dupri wrote and produced everything on Totally Krossed Out, the Kris Kross album that came out in March of 1992. Dupri had been to a concert and noticed that "people were just into jumping." In the Bronson book, Dupri says that he wrote "Jump" in an hour, though he probably spent a whole lot longer putting together the beat. Like most other rap hits of that early-'90s moment, "Jump" is a stitched-together collection of samples, and in an age where all those samples have to be cleared, it would probably be prohibitively expensive to release. The main instrumental hook of "Jump" is a needling, wobbling synth-loop that's taken from "Funky Worm," the 1973 funk workout from former Number Ones artists Ohio Players. ("Funky Worm" peaked at #15. Before "Jump," "Funky Worm" samples had already appeared on a couple of N.W.A tracks.)

The little squelches in Jermaine Dupri's "Jump" beat come from the intro to "I Want You Back," the Jackson 5's debut single. I never noticed the "I Want You Back" sample when "Jump" was new, but maybe Dupri figured out how to work in a subconscious connection to a previous generation of baby stars. The busy "Jump" drums, meanwhile, draw on at least four different songs -- James Brown's "Escape-Ism," the Honey Drippers' "Impeach The President," Schoolly D's "Saturday Night," Cypress Hill's "How I Could Just Kill A Man." Apparently, there are Doug E. Fresh and Digital Underground samples in there, too.

It's hard to pick all that stuff out. The "Jump" beat is funky chaos. It's not as overwhelming as the noise-collage klaxons that the Bomb Squad made for Public Enemy, but it has some of that same bedlam working for it -- all these different half-remembered sounds piled up together, transformed into something deceptively simple and hard-hitting.

The "Jump" beat doesn't register as something too complicated because the song itself is so direct. The hook is just Kriss Kross informing you that they will make you jump, and that central chant is about the simplest dance instruction possible. A song like that doesn't exactly need a visual demonstration, but the "Jump" video made it even more obvious. That video is visually striking and memorable -- a bunch of guys in a studio, outlined against a white backdrop, jumping in time with the chorus. It also shows these two little mean-mugging kids rocking those backwards clothes and strutting across snowy fields, projecting a confidence that didn't look rehearsed.

Kris Kross were not the first kiddie-rap group, and they weren't the first kiddie-rap group to make the charts, either. On "Jump," though, Kris Kross make it plain that they're the hardest kiddie-rap group. On the first line of the first verse, Mac Daddy takes aim at Kris Kross' kompetition: "Don't try to compare us to another bad little fad." The previous year, the New Edition/Bell Biv DeVoe member Michael Bivins had discovered Another Bad Creation, another group of cute rapping kids from Atlanta, and they'd released their album Coolin' At The Playground Ya Know! ABC sang and rapped, and Bivins presented them as a new version of New Edition, updated for a new jack swing era. It would've been natural to try to compare Kris Kross to this other bad little fad, but Kris Kross weren't having it.

In the video for their biggest hit "Iesha," the members of Another Bad Creation had worn their clothes inside out. ("Iesha" peaked at #9. It's a 6.) On his "Jump" verse, Mac Daddy calls them out. Kris Kross' goofy-ass fashion decision, Mac Daddy argued, was much cooler than what those ABC chumps were doing: "Everything is to the back with a little slack/ Cause inside-out is wiggida-wiggida-wiggida-wack." (The "wiggida-wiggida" thing was Mac Daddy riffing on another rap trend, the tongue-flipping style popularized by the Brooklyn duo Das EFX. Das EFX's highest-charting single, 1992's "They Want EFX," peaked at #25.) And Kris Kross also wanted you to know that there was nothing new jack swing about them: "I come stompin' with something pumpin' to keep you jumpin'/ R&B, rap and bullcrap, is what I'm dumpin'."

Now: Kris Kross were not hard. In 1992, rap's biggest non-crossover star was probably Ice Cube, whose combination of street nihilism and revolutionary rhetoric set hardness standards that two little Atlanta kids couldn't possibly hope to match. Taking all those shots at Another Bad Creation, though, Kris Kross defined their own playing field. They only had to sound tough in comparison to these other little kids, and they pulled that off.

Of course, taking shots at that other crossover kiddie-rap group helped Kris Kross become the biggest crossover kiddie-rap group of all time. "Jump" consciously stays away from previously established crossover moves. There's no melody on "Jump," no singing. It's pure rap music, and it works on that level. "Jump" isn't a dazzling work of lyricism or anything, but it's got energy and confidence and an infectious stick-in-your-head hook. The lyrics are pretty funny -- "a young lovable, huggable type of guy," "two little kids with a flow you ain't ever heard" -- but Kris Kross deliver them with straight-up severity. As a 12-year-old, this was exactly what I wanted to hear. I was obsessed, and so was every other kid I knew.

I don't think I can do justice to the omnipresence of "Jump" in the spring and summer of 1992. Kids would just greet each other by rapping lines from "Jump." When I started going to bar mitzvahs, there were stories about the kids who wore their tuxedos backwards. (I never saw this, but other kids swore it happened.) I can vividly remember when Baltimore mayor Kurt Schmoke, whose daughter was in my math class, gave Kris Kross the key to the city. I thought it was the coolest thing.

The "Jump" single came out in February of 1992, almost two months before the Totally Krossed Out album. It took a couple of months for "Jump" to gather steam, but after Kris Kross performed the song on an early-April episode of In Living Color, the song suddenly soared up the chart, leaping from #61 to #12 in a single week. (Kris Kross probably would've been prime targets for In Living Color mockery if they hadn't actually been on the show; whoever got them booked was very smart.)

"Jump" rose to #1 at a dramatic moment. Four days after "Jump" registered its first week atop the Hot 100, a jury in Simi Valley, California acquitted the four cops who'd been caught on tape savagely beating Rodney King. This was just the latest in a long history of cops and vigilantes getting license to violently victimize the working-class Black and Latino people of Los Angeles, and LA wasn't going to take it anymore. Immediately after the verdict, much of Los Angeles rose up. The LAPD essentially sat back as people burned and looted for days on end. After five days, when the National Guard finally took control, 63 people had been killed, and thousands more were arrested.

The spring of 1992 was tense. My parents, all worked up after watching new coverage and convinced that the same racial unrest was about to come to Baltimore, made me stay home for days on end. In the aftermath of the LA uprising, professional moral watchdogs tried to pin blame on reality-rappers like Ice Cube and Ice-T, who'd been calling out police brutality in music for years. So there's something oddly beautiful about how just about every 12-year-old in America spent that time obsessing over these two Black kids from Atlanta and their song about jumping. Music doesn't change everything, and the problems that led to the Los Angeles uprising have not gone anywhere. A cultural phenomenon like "Jump" might be more of a distraction than anything, but I'd like to think it's significant that so many of us fell in love with that song when we did.

That whole narrative, however is complicated by the fact that a group of white guys from LA soon hit with their own song about jumping. And it's complicated even more because that white-rap song about jumping is some kind of knucklehead masterpiece. House Of Pain's "Jump Around" came out a couple of week after Kris Kross' "Jump" hit #1. House Of Pain didn't just sample Kris Kross labelmates Cypress Hill on "Jump Around"; they got Cypress Hill's DJ Muggs to produce the adrenaline-rush track. A few months later, "Jump Around" peaked at #3. (It's a 10.)

House Of Pain did not steal Kris Kross' thunder. A year after its release, Totally Krossed Out was quadruple platinum, and the "Jump" single had sold two million copies. A "Jump" VHS single moved 100,000 units, and Sega marketed its Sega CD system with Kris Kross: Make My Video, a widely panned game where you could edit Kris Kross videos. Kris Kross spent the summer of 1992 on tour with Michael Jackson, and they also appeared alongside Jackson and Michael Jordan in Jackson's "Jam" video. ("Jam" peaked at #26. A couple of members of Another Bad Creation had been in Jackson's "Black Or White" video. In the great kiddie-rap wars of 1992, Michael Jackson was Switzerland.)

But the Kris Kross phenomenon was not built to last. Even with all that hype, Kris Kross never returned to the top 10 after "Jump." The duo's extremely catchy follow-up single "Warm It Up" came close, peaking at #13. But the goofy story-rap "I Missed The Bus" only made it to #63, and even those of us who'd loved "Jump" clowned the video heavily. Those monsters looked stupid.

A little more than a year after Totally Krossed Out, Kris Kross released their second album Da Bomb. History remembers Da Bomb as a brutal sophomore-jinx fall-off. In the time between Totally Krossed Out and Da Bomb, Dr. Dre's The Chronic reshaped the pop landscape, establishing the overwhelming popularity of nihilistic reality-rap. In his production for Da Bomb, Jermaine Dupri tried to update Kris Kross' sound, integrating the smooth G-funk of the moment. People made jokes, but Da Bomb was not a flop. The album went platinum, and lead single "Alright," which featured dancehall toaster Super Cat, peaked at #19. Also, that same year, Kris Kross starred in a Sprite commercial that was on all the time. Kris Kross weren't doing Totally Krossed Out numbers anymore, but they were maintaining.

Kris Kross followed Da Bomb with 1996's Young, Rich & Dangerous. That album went gold, and lead single "Tonite's Tha Night" peaked at #12, which made it the duo's biggest non-"Jump" hit. But everyone else associated with Kris Kross profited from the success of "Jump" more than Kris Kross themselves. Jermaine Dupri's father Michael Mauldin, for instance, became president of the Black music division at Columbia. Dupri himself started his So So Def imprint in 1993. One of the first stars at So So Def was Da Brat, a Chicago rapper who won an MTV-sponsored rap contest in 1992 and, as the grand prize, got to meet Kris Kross. Kris Kross introduced her to Dupri, and Dupri essentially marketed her as a female version of Snoop Doggy Dogg. By 1994, Da Brat was a star. (Brat's highest-charting single, 1994's "Funkdafied," peaked at #6. It's a 7.)

Jermaine Dupri and So So Def went on a hitmaking run that lasted for years. As a producer and label executive, Dupri became so successful that he eventually attempted a rap career of his own. (As lead artist, JD's highest-charting single is the 1998 Da Brat/Usher collab "The Party Continues," which peaked at #29. As a producer and songwriter, he'll be in this column many more times.) On Clipse's 2001 track "Let's Talk About It," Dupri claimed that he was "still spendin' that Kris Kross cream." By that time, Kris Kross were a distant memory.

"Jump" was a moment in time. At my senior prom in 1998, the DJ threw on "Jump" and got what must've been the biggest reaction of the night. Six years after its release, "Jump" was already a nostalgia-trigger. Kris Kross never released another album after 1996. It's got to be an absolute mindfuck to be considered washed-up at 17. I can't find a whole lot of information about what the two Chrises of Kris Kross were doing after that last album came out. In 2013, though, Jermaine Dupri threw a 20th-anniversary bash for his So So Def label at Atlanta's Fox Theatre, and that show featured a reunited Kris Kross performing "Jump" one last time.

Two months after that anniversary show, Chris "Mac Daddy" Kelly died of a drug overdose in his Atlanta home. He was 34 years old. Chris "Daddy Mac" Smith is alive and well, and he apparently owns a clothing line called Urban Muse. Smith's Instagram shows that he's looking pretty good, albeit totally unrecognizable, these days. I wish him well. Kris Kross weren't titans or anything, but their success was an important moment in rap history, and their one big song is still pretty great.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: In 2007, Remy Ma released her own version of "Jump," which turned the song's meaning into something else. Here's the video:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=bRaxco6nf10&ab_channel=RemyMaTV

(As lead artist, Remy Ma's highest-charting single is the 2016 Fat Joe/French Montana collab "All The Way Up," which peaked at #27. As a member of Terror Squad, Remy will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: On his 2008 single "Hussle In The House," the late Nipsey Hussle rapped over a tweaked version of the "Jump" beat. Here's the video:

(Nipsey Hussle's highest-charting lead-artist single is the 2009 Hit-Boy/Roddy Ricch collab "Racks in the Middle," which peaked at #26. That same year, Nipsey also appeared posthumously on DJ Khaled's "Higher," which peaked at #21.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Justin Timberlake rapping "Jump" at Mila Kunis in the 2011 movie Friends With Benefits:

(Justin Timberlake will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Wale rapping over the "Jump" beat on his 2011 mixtape No Days Off:

(As lead artist, Wale's highest-charting single is the 2013 Tiara Thomas collab "Bad," which peaked at #21. As a guest, his biggest hit is Waka Flocka Flame's 2010 track "No Hands," which peaked at #13.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Brockhampton interpolating "Jump" on "MVP," their contribution to the godawful 2021 film Space Jam: A New Legacy:

(Brockhampton's highest-charting single, 2019's "Sugar," peaked at #66.)

THE NUMBER TWOS: Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody," a #9 hit upon its 1975 release, became a bigger hit after the Freddie Mercury's death and the song's appearance on the Wayne's World soundtrack. "Bohemian Rhapsody" reached a new peak of #2 behind "Jump." It's a 9.

En Vogue's spiky, swaggering put-down "My Lovin' (You're Never Gonna Get It)" also peaked at #2 behind "Jump." It's another 9.

The Red Hot Chili Peppers' beatific heroin lullaby "Under The Bridge" also peaked at #2 behind "Jump." It's an 8.